Created with BioRender.com

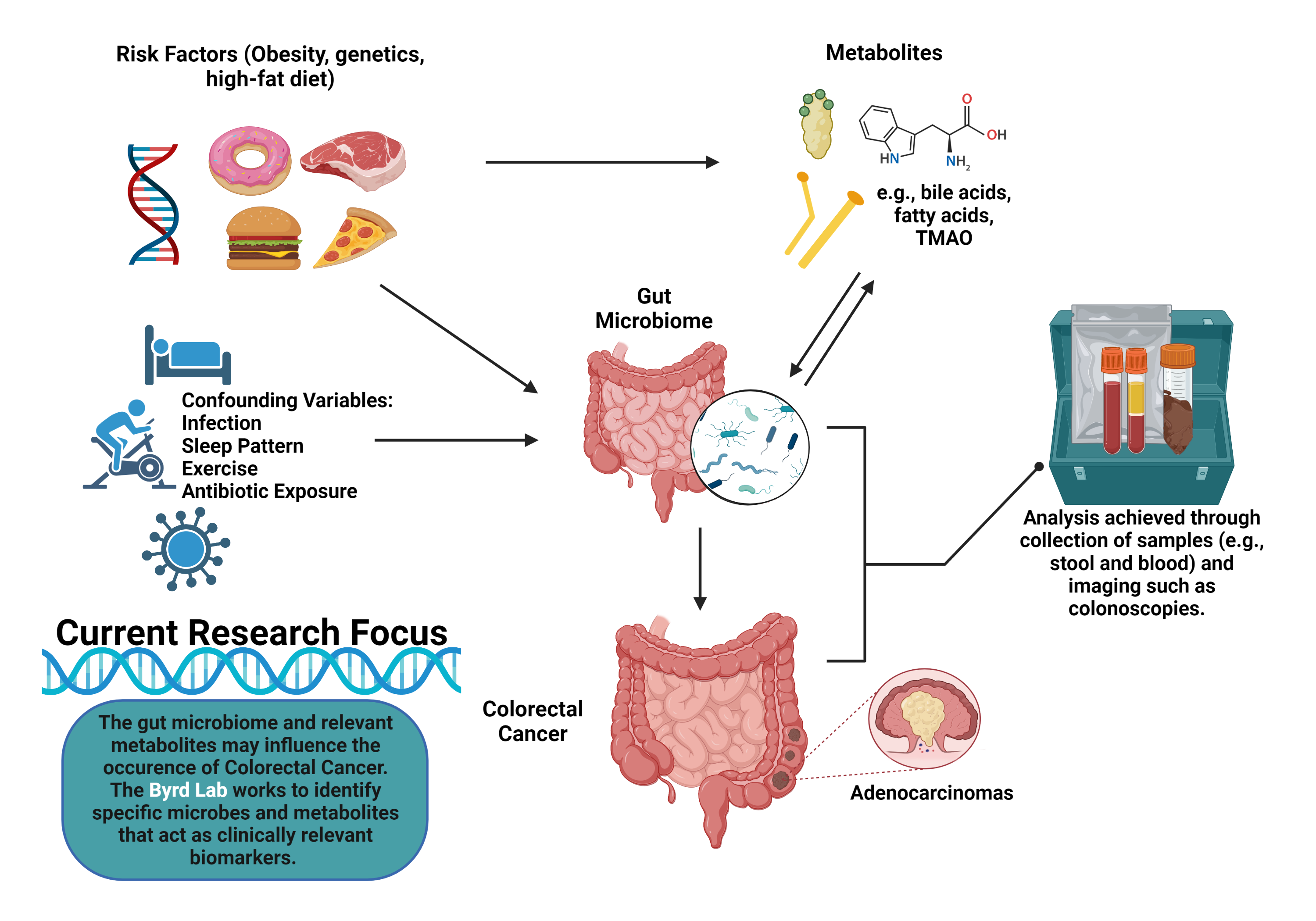

The gut microbiome is the largest collective of microbes in the human body, composed of trillions of microorganisms, from bacteria and archaea to viruses and fungi. Oral bacteria may colonize the gut such as via chewing and swallowing or by entering the bloodstream.1 Disruptions to intestinal permeability, gut bacteria composition, or the gut environment may also promote flourishment of oral-originating microbes in the gut.2 These microbes cohabitate and interact with their host’s cells to influence health and disease. Microorganisms such as the genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Bacteroides may help maintain healthy gut conditions and regulate disease-causing intestinal bacteria, for example. Certain medications (including antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and radiation) and other adverse exposures such as poor diet can disrupt the normal gut flora. This imbalance in the gut may lead certain opportunistic pathogenic microbes, including Clostridium difficile, to thrive, triggering disease. Recent scientific literature suggests that the gut microbiome may be associated (both positively and inversely) with cancer risk and outcomes as well.3 For example, the oral pathogen Fusobacterium nucleatum may be implicated in colorectal cancer development and progression.4 Mechanisms that may explain associations between microbes and cancer include the production of certain metabolites like bile acids and short-chain fatty acids and direct interactions with the host’s immune system. Further studies are needed to solidify our understanding of both harmful and protective mechanisms of action.

Importantly, the microbiome can be manipulated through interventions that alter diet, physical activity and other lifestyle factors.5 It can also be altered through the introduction of specific microbes or microbial energy sources such as pro and prebiotics, respectively.5 When we determine the relationships between the gut flora and cancer risk, progression, and outcomes, we may be able to target and manipulate the gut microbiome of the host to not only improve outcomes for current patients but to guide recommendations to help prevent cancer development in the first place.

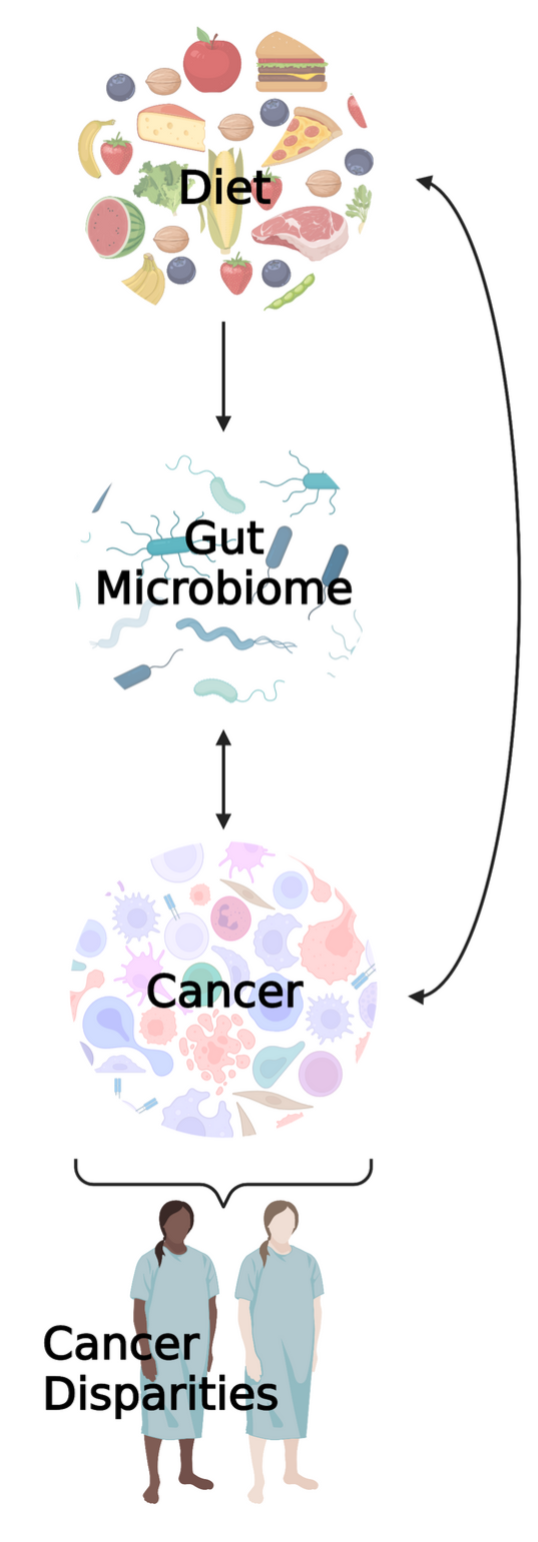

The Byrd Lab studies the interrelationships between diet and other lifestyle factors, the gut microbiome and associated metabolites, and cancer, with particular focus on cancer disparities. Associations between the microbiome and cancer have mainly been cross-sectional to date (i.e., microbiome and cancer measurements occur at the same time, such that we do not know which came first) and largely lack representation of historically underserved populations, such as Blacks/African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos. To address these gaps, we employ longitudinal research designs, with recruitment efforts focused on minority populations, to help advance etiologic and prognostic biomarker-related microbiome research. Our ultimate goal is to identify clinically relevant microbiome features (e.g., certain microbial taxa or microbially-related metabolites) that may predict cancer diagnosis, cancer treatment responses, and even survivorship outcomes. Actively recruiting studies include:

References:

1. Park DY, Park JY, Lee D, Hwang I, Kim H. Leaky Gum: The Revisited Origin of Systemic Diseases. Cells. 2022;11(7):1-17. doi:10.3390/cells11071079

2. Mo S, Ru H, Huang M, Cheng L, Mo X, Yan L. Oral-Intestinal Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer: Inflammation and Immunosuppression. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15(February):747-759. doi:10.2147/JIR.S344321

3. Flemer B, Warren RD, Barrett MP, et al. The oral microbiota in colorectal cancer is distinctive and predictive. Gut. 2018;67(8):1454-1463. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314814

4. Komiya Y, Shimomura Y, Higurashi T, et al. Patients with colorectal cancer have identical strains of Fusobacterium nucleatum in their colorectal cancer and oral cavity. Gut. 2019;68(7):1335-1337. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316661

5. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

Created with BioRender.com